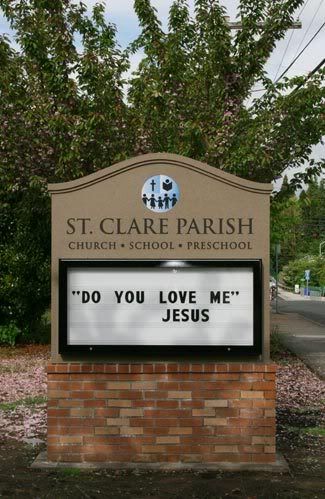

Yesterday, in a speech delivered at my younger brother’s college graduation ceremony in Tacoma, Washington, I noticed the school’s President attempting to lead his audience in prayer. Not a typical prayer, mind you—though it did assume the unmistakable tone and diction of invocation—but this was more of a politically correct sort of modern-day adaptation of something resembling a prayer. The interesting bit was the preface he gave before embarking. He said something to the effect of: “Today, we have many ways of defining the powers that be. Some call those powers God. Others say that they can be found in the extraordinary and breathtaking constructs of nature. And some say those powers are evident in the best of human kind… Now, let us take a moment and reflect...”

“Source of life…” he continued, leading into the most diplomatic and amorphous of ‘prayers.’

‘Source of life?’ I thought. Ha! Only when someone is bending over backwards to be p.c. do phrases like ‘source of life’ come into play in this context (find and replace ‘God’ with ‘Source of life’—that’s cute). But this was a manifestation of something that I’ve been thinking about lately:

What is the proper/acceptable role of prayer/spirituality in a society that is clearly shying from religious ideals and moving gradually toward that of the non-theist?

In this case, the adapted prayer, which effectively transcended denomination and avoided reference to any given faith altogether, was actually inclusive of non-believers. I imagine there was a small minority of attendees who were miffed that the school President didn’t recognize God, the one true ‘God,’ but the general feeling was a good one and a nostalgic one. As people bowed their heads, shut their eyes, or became otherwise silent and attentive, it was clear that the ears of 8,000 people were somehow tuned to the distinct and familiar tone of religious oration, and though I am an atheist and took the speaker to be (maybe) non-religious too, I appreciated the opportunity to reflect and take part in what felt like a viable kind of shared spirituality—something that Atheists typically do value despite characterizations to the contrary.

Monday, May 14, 2007

Sunday, May 6, 2007

Dawkin's 'Scale of Belief'

Not only is Richard Dawkin's proposed 'Scale Of Belief' well constructed and useful, I think it apt to couple it with Bertrand Russell's 'Celestial Teapot' analogy. So many of the commonly used 'god-analogies' created and employed by non-believers (unicorns, flying spaghetti monster, etc.) are at worst condescending, and at best aesthetically unpleasing. Russell's teapot analogy, on the other hand, is elegant and serves its purpose better than most.

The parable goes: Somewhere between Earth and Mars there is a perfect china teapot in an elliptical orbit around the sun.

The point of this analogy is to show that while this claim may be difficult to disprove (like certain claims about God), the person making the claim would undoubtedly have a difficult time garnering support for such a belief. And while it would hardly be worth anyone's time to try and disprove this propostion (which probability seems to build a strong case against) the burden of proof would nonetheless rest on the claim-staker, were it of any consequence.

Claims about God, while similarly far-fetched, are considered to be of ultimate consequence. Still, it is not the responsibility of scientists or philosophers, or Safeway cashiers to disprove them, just as it is not anyone's responsibility to disprove the infinite number fathomable possibilities.

With Russell's analogy in mind, here is Dawkin's 'Scale of Belief.'

1. Strong theist. 100 per cent probability of God. In the words of C.G. Jung, "I do not believe, I know."

2. Very high probability but short of 100 per cent. De facto theist. "I cannot know for certain, but I strongly believe in God and live my life on the assumption that he is there."

3. Higher than 50 per cent but not very high. Technically agnostic but leaning toward theism. "I am very uncertain, but I am inclined to believe in God."

4. Exactly 50 per cent. Completely impartial agnostic. "God's existence and non-existence are exactly equiprobable."

5. Lower than 50 per cent but not very low. Technically agnostic but leaning towards atheism. "I don't know whether God exists but I'm inclined to be skeptical."

6. Very low probability, but short of zero. De facto atheist. "I cannot know for certain but I think God is very improbable, and I live my life on the assumption that he is not there."

7. Strong atheist. "I know there is no God, with the same conviction Jung 'knows' there is one."

Dawkins says, "I'd be surprised to meet many people in category 7, but I include it for symmetry with category 1, which is well populated."

The parable goes: Somewhere between Earth and Mars there is a perfect china teapot in an elliptical orbit around the sun.

The point of this analogy is to show that while this claim may be difficult to disprove (like certain claims about God), the person making the claim would undoubtedly have a difficult time garnering support for such a belief. And while it would hardly be worth anyone's time to try and disprove this propostion (which probability seems to build a strong case against) the burden of proof would nonetheless rest on the claim-staker, were it of any consequence.

Claims about God, while similarly far-fetched, are considered to be of ultimate consequence. Still, it is not the responsibility of scientists or philosophers, or Safeway cashiers to disprove them, just as it is not anyone's responsibility to disprove the infinite number fathomable possibilities.

With Russell's analogy in mind, here is Dawkin's 'Scale of Belief.'

1. Strong theist. 100 per cent probability of God. In the words of C.G. Jung, "I do not believe, I know."

2. Very high probability but short of 100 per cent. De facto theist. "I cannot know for certain, but I strongly believe in God and live my life on the assumption that he is there."

3. Higher than 50 per cent but not very high. Technically agnostic but leaning toward theism. "I am very uncertain, but I am inclined to believe in God."

4. Exactly 50 per cent. Completely impartial agnostic. "God's existence and non-existence are exactly equiprobable."

5. Lower than 50 per cent but not very low. Technically agnostic but leaning towards atheism. "I don't know whether God exists but I'm inclined to be skeptical."

6. Very low probability, but short of zero. De facto atheist. "I cannot know for certain but I think God is very improbable, and I live my life on the assumption that he is not there."

7. Strong atheist. "I know there is no God, with the same conviction Jung 'knows' there is one."

Dawkins says, "I'd be surprised to meet many people in category 7, but I include it for symmetry with category 1, which is well populated."

Friday, May 4, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)